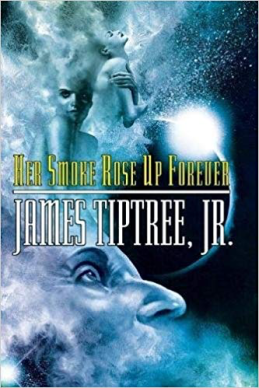

James Tiptree, Jr. — aka Alice Sheldon — wrote a story back in 1974 called “Her Smoke Rose Up Forever.” It’s a tale about memory. Scenes from a life play out one after another: a boy on his first duck hunt, failing miserably; a young man in his first, eager sexual encounter, failing miserably; a man back from war proposing, finally, to the woman he loves, failing miserably…you get the idea. Framing this jumbled litany of humiliation and disappointment is the gradual realization that all of these memories are playing out in a sort of repeating loop, observed by — perhaps even instigated by — some unknown presence: alien researchers perhaps? Or even just alien sightseers, feeding on the memories of the long gone inhabitants of a dead world? Because the earth is dead, a burnt out cinder. All that remains are memories.

But — and here’s the gut punch — the only memories left are unpleasant ones. Only the horrible stuff, incidents our protagonist would rather forget. Instead, he gets to live them out again and again.

A hellacious vision. Thanks, Alli.

But still, a fascinating premise. Sad memories, painful memories, seem to have a disproportional staying power. Enjoyable memories can linger as well, but they are less vivid, less intrusive. It seems like we have to go looking for those, we have to coax them to the surface. But deeply unpleasant memories find us. We have no idea when they might swim into sudden focus. It’s like they’re always lurking in the shadows, just around the next corner.

There’s a good reason, of course, why we would be predisposed, genetically, to have a better memory for the unpleasant things. After all, unpleasant things are often dangerous things, and it’s an adaptive advantage to avoid danger. If a situation feels unpleasantly familiar, you’ll tend to shy away from it and not repeat it. As for joyous memories of good times, well, it’s nice to remember them, but it’s not usually a matter of life or death. Lack of joy might kill you in the long run, but it’s only a gradual death and it won’t necessarily interfere with your ability to pass on your genetic code.

But danger? That can kill you right now, the immediate termination of your particular configuration of base pairs. So we avoid unpleasantness. It’s baked in, a survival skill.

And to avoid it, we have to recognize it. We have to remember. If I were an alien, researching the former dominant species of an extinct planet, I might focus on exactly that: what drove their worst memories? What were they so afraid of?

***

So how does this concept relate to stories? Does this predisposition explain why we have such an appetite for tragedy, for conflict-driven narratives? Such a fascination with crime and horror and dystopian futures? Could be. I’d admit that there are other factors. Catharsis plays into it — and the guilty thrill we might feel at experiencing someone else’s misery while knowing it isn’t our own. But it isn’t hard to see how these pleasures might have their roots in the original preoccupation. Suffering fascinates us because it’s important to our survival. We rubberneck the freeway accident because, at some level, we know that could be us.

And if it might kill us, we need to know about it.

***

Footnote: It feels worth mentioning that some of our most persistent personal memories are of rejection and humiliation, which might not correlate directly with situations of danger or physical threat. We don’t, as a rule, die of embarrassment. But being rejected or humiliated, at least publicly, can be correlated with social ostracism, which could be almost as bad as death. In terms of passing your genetic material on to the next generation, it could be exactly as bad as death. The process of natural selection really doesn’t put a priority on our happiness. It’s only concerned with us surviving long enough to procreate.

***

Another Footnote: I would accept that being joyless might be a hindrance to finding companionship and a partner for procreation. But this seems to me a very modern view of our mating relationships. While romance isn’t very new, it’s pretty new compared to our time as a species, and there’s good reason to believe that marriage probably developed more as a practical arrangement and didn’t necessarily require having a winning personality or a great outlook on life. Fortunately, we’ve progressed beyond that point, mostly — but that’s a subject for another time.